Educational writer Fiona Scott-Barrett blogs for us about her earnings

I trained as a teacher of English as a Foreign Language nearly forty years ago, and have worked in various sectors of that field since 1979. My first EFL textbook was published in 1991 and, in the ensuing 27 years, I have written a further ten main titles, all of which have been published by leading educational publishers. EFL textbooks are nearly always accompanied by other components – teacher’s books, workbooks, audio materials, digital downloads, online interactive materials, and so on – and, in common with many EFL writers, I have also been involved in writing these.

Throughout most of the period in which I have worked as a professional writer, it has been necessary to supplement my writing income with part-time EFL teaching work, or by other paid employment. For a halcyon interlude of about seven years, I managed to support a family of three on my writing income alone, but this was possible only because I lived in Greece, where living costs were considerably lower than in the UK.

Throughout most of the period in which I have worked as a professional writer, it has been necessary to supplement my writing income with part-time EFL teaching work, or by other paid employment. For a halcyon interlude of about seven years, I managed to support a family of three on my writing income alone, but this was possible only because I lived in Greece, where living costs were considerably lower than in the UK.

A brief explanation about how EFL authors are paid may be helpful in understanding why their incomes are frequently low. This is generally not because sales figures are poor; publishers research their markets before commissioning textbooks and, although some titles may perform less well than expected, it is relatively rare for a textbook to sink without trace due to low sales. The first problem is that authors’ royalties are paid as a percentage of sums received by the publishers, not as a percentage of the published price. Due to deep discounting, a textbook that retails at 30 Euros per copy may earn the publisher only 12 Euros and the author(s) will thus receive 1.2 Euros per copy.

The second problem is that main textbooks are frequently co-authored, and any royalty is split between the authors. If two authors collaborated on the book given as an example in the paragraph above, each would earn 0.60 Euros per copy sold. The other components are often commissioned on a flat fee basis, and are also often farmed out to authors who did not write the main book. These components add value to the product, but do not result in any extra income for the main writer(s).

Despite these factors, it was, and perhaps still is, possible for a handful of authors to do well out of EFL titles. Those, like me, whose books are aimed at niche sectors within the main EFL market, such as business English skills, or exam preparation, rarely achieve large enough sales to offset the problem of their income being based on sums received. In 2001, my best-ever year, I earned around £20,500 from writing, 75% of which came from royalties and advances, as opposed to fees. This was because the royalties were on titles I had authored alone, and also included royalties paid on audio cassettes or CDs, which were good earners as they were not heavily discounted to wholesalers.

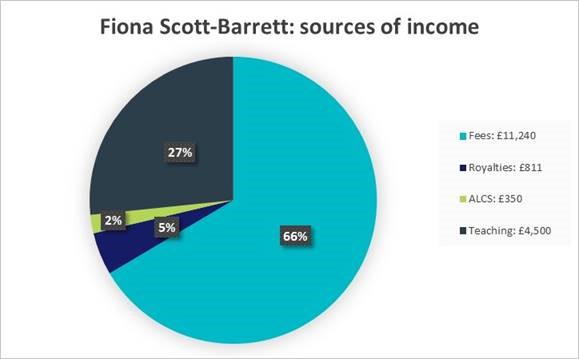

In recent years, the situation has been made more difficult by an increasing trend to put larger writing teams together to handle multi-component courses, with more and more of those components being paid on a fee basis rather than through royalties. In order to write this blog, I dug old financial records out of my archives. These revealed that, in the period 1995-2000, 73 per cent of my writing income came from advances or royalties, with only 27% from fees. In contrast, in the tax year 2017/8, 92 per cent came from fees (or 66 per cent if teaching is taken into account). My gross writing income for the most recent tax year was £12,401. Needless to say, I had to look for other income streams, and supplemented my writing income by going back into part-time teaching.