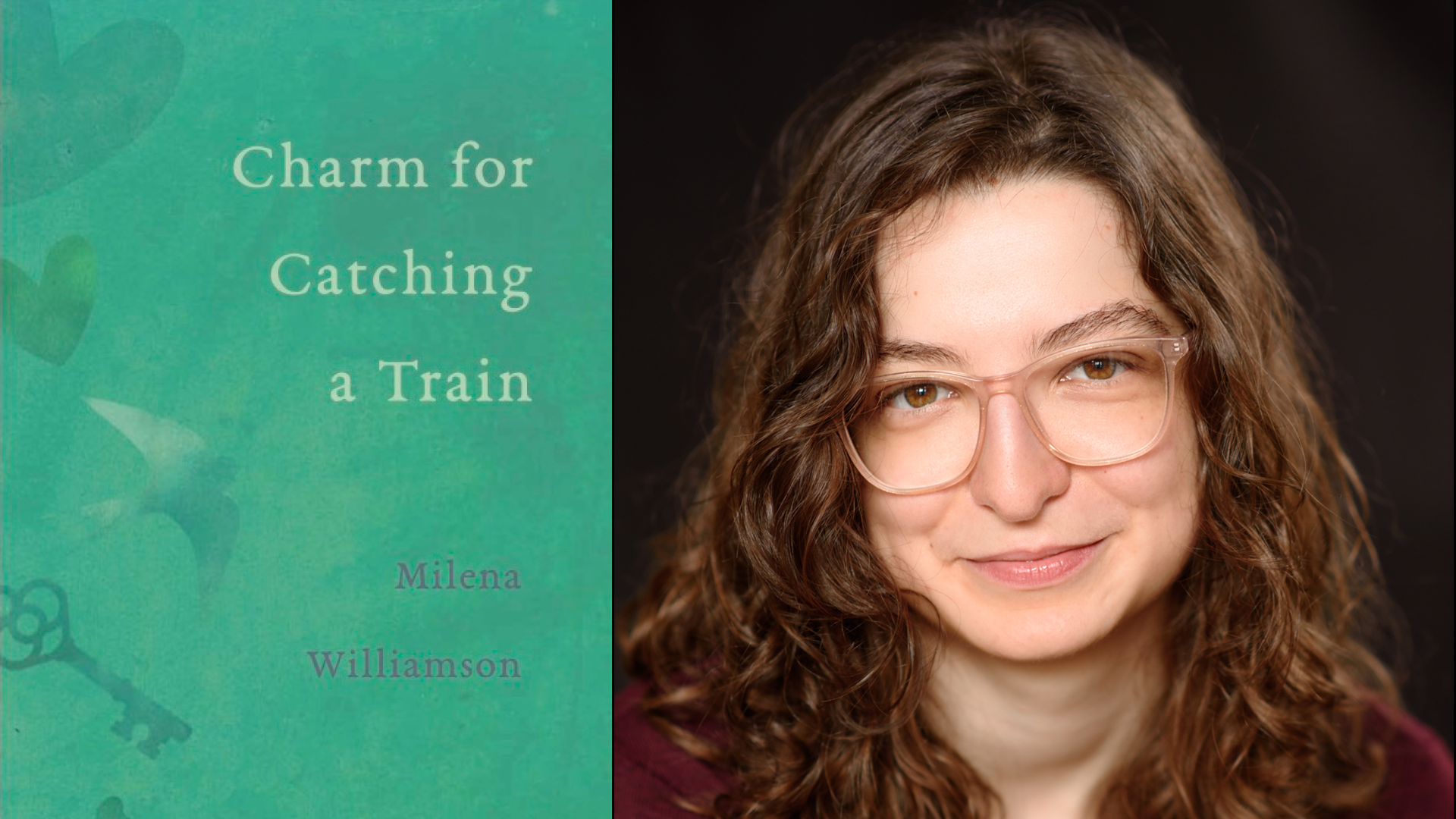

First published in The Author (Autumn 2023 – vol 134.3)

Take-home assignment: Come up with a list of topics

and themes you don’t like to explore.

What are your boundaries and your nos?

I recently attended a series of what I initially perceived to be fairly redundant online workshops on performance and poetry. In the most challenging one, which even trumped free-writing to Mongolian throat singing in the dark, we (a group of South Asian writers) were asked to do an impromptu mime improv, whereby I had to wrestle with my bed in a thin-walled hotel room in Tokyo and open up imaginary French doors (to this day I am not exactly sure what they are, and Google has only shown me the ugly ones in white plastic), then step through, and let words fall out how they might, whatever they may be.

Having been used to poetry workshops which were solely about the poetry, where we actually wrote poems within the given time, and had ample time to listen to each other’s works (I believe this to be the most crucial part of any workshop), I was beyond critical, wilfully resistant. Reader, I simply did not want to be there. But opening up to these workshops and going beyond myself yielded an interesting thought. It was something I had never taken the time to consider, let alone discuss with fellow poets. It came about in response to the take-home assignment we were given, which made me really think: what are my boundaries, when it comes to writing? What would I say ‘no’ to?

Like many poets I do not like to diminish my poetics to ‘topics’ and ‘themes’, which is why the question ‘so what do you write about?’ is such a pain to answer. I normally respond with a curt: ‘I write about my mother’. And, indeed I do write about my mother but she is neither a topic nor a theme. In my poetry she just is, alongside my exploration of queerness, what it means to be Nepali, my twinky body, my abusive addict father; or my experiences of being working class.

But the prompt made me conscious of this fact: existing alongside these things are the things that are not in my poetry. Like dark matter, like the thin spaces between the pages of every book, the things that I have consciously or unconsciously omitted still take up some space in the architectures of my work. What were these things that just aren’t in my poetry? The thought reminds me of Maggie Nelson’s articulation (in The Argonauts) of Wittgenstein’s idea that ‘the inexpressible is contained – inexpressibly! – in the expressed.’

I had always felt that my writing should, no must, have the power to transcend all boundaries. No one has the right to tell me there are things I cannot write about, especially myself. I have long been happy writing about anything and everything and I believed that all the rooms I contained, the rooms that contained my shaky childhood, the rooms with all my sticky unrequited love for straight men, the rooms with my angry father – I considered all these rooms of my multitudes were open to me.

Like dark matter, like the thin spaces between the pages of every book, the things that I have consciously or unconsciously omitted still take up some space in the architectures of my work. What were these things that just aren’t in my poetry?

In the past, I have vehemently rejected Barthes’ theory that the ‘Author’ is an autocratic figure, that the ‘Author’ ‘imposes a limit’ because their work is ‘tyrannically centred on the author, their person, their life…’ This, to me, was absurd. Should we not draw inspiration from ourselves? Rather than imposing a limit, doesn’t this enable rich and audacious poetry? My life, experiences and memories, the light of a warm evening, even the lazy itchy afternoons fill up a bottomless well; when called upon, I will send down my empty bucket, knowing that it will bring with it the waters – brothy, clear or turmeric yellow – that nourish my poetry.

Still, out of obligation I contrived a list of all my boundaries and ‘nos’, the ‘themes’ I don’t like to explore: illness and sickness; the mind and intrusive thoughts; writing out the things I’m afraid of. But I then had a conversation with another South Asian poet on the programme, which elucidated that the issue is not so much the boundaries I set for my writing as those I should set for myself. I do need dams for my overflow of feeling.

The difficulty is protecting ourselves from ourselves, especially when the dominant strain in poetry is confessional. It has become a given that poets disclose or air out their hearts and souls in their work. Claire Armitstead praises Ocean Vuong, for instance, for ‘weaving the lines and verse with the inflections of his own self’ – and my own poetry was set alight by his audaciously personal poems on masturbation, blowjobs, and the violence that manifests from intergenerational trauma and the effects of the Vietnam war.

I see this weaving of one’s life into lines in the works of all my favourite poets: the fraught and fulfilling complexity of fatherhood in Raymond Antrobus’ work; how beautiful and tragic it is to reckon with your mother’s scorn at your queerness in ‘The Window’ by Mary Jean Chan; how to reclaim a body that has been forcefully breached in Paul Tran’s incredible collection All The Flowers Kneeling (2022).

There is of course nothing wrong with weaving life into poetry. But I wonder how these poets protect themselves from giving too much of themselves away. It may seem strange to describe writing in these terms when it is more often seen as restorative, even healing. Annie Ernaux, for instance, states that all her writing stems from an ‘urgency to save something’ and that she writes in order to cope: ‘When you’re locked to the present, a diary is a type of exit we give ourselves – an escape’. Some poet friends of mine even went to a workshop where the first thing they were asked to do was write down the most personal thing that they will never tell anyone, and share it with the room. Why? Because writing purges all shame. Because writing is expected to help us digest and reclaim control over difficult experiences. ‘Did writing these poems help you to process [your mother’s] passing?’, Vuong was asked in response to his second collection, Time is a Mother. Writers of colour are especially expected to cater to the market for the confessional, for an outpouring, especially in telling the stories of their struggles. There is pressure to perform ‘a kind of ethnography in their work’, and then to somehow come up on top through writing, because writing salvages. Writing saves.

There is pressure to perform ‘a kind of ethnography in their work’, and then to somehow come up on top through writing, because writing salvages. Writing saves.

But writing can exhaust and be exhausted; should healing come to you as a byproduct then that is wonderful but it is dangerous to rely on it as a stringent tool for healing. Take experiences of trauma: how do we avoid repeatedly damaging ourselves when we tap into those ripping experiences when writing? By tapping into trauma as a praxis, are we retraumatising ourselves? Ultimately, how can we stop ourselves from offering up too much of ourselves – and how do we know how much is too much?

I know first-hand the healing power of writing, so that question is difficult for me to answer. The first time I wrote something that drew from my own life – an amateurish short story filled to the brim with closeted angst – it all began to click. There was a release from my parents’ divorce, my father’s abandonment and my mother’s pain. Since then, writing has always been a solace. I have cried, writing poems in the earliest hours of the morning, relishing the catharsis. I still write whenever I find that my sense of self is in flux, whether it is after an earthquaking fight with my mother or being heartbroken by another toxic softboi.

Recently, I really needed to write. The week after my graduation I found myself in a suspended vacuum of intrusive thoughts and fatty anxiety, but writing in my notebook anchored me; even if it is just writing down affirmations and mantras. I hope that everyone can turn to a page where they subdue all that is coming for them. But can writing be like an opiate? What if our synapses become numb to its effects? And so it is more effective to seek healing in life, which will carve out space for writing to be joyful.

Until the pandemic, I subscribed and submitted to the notion that mental health was a western concept. My mum still doesn’t understand anxiety, and there is apprehension around mental health in migrant communities. But I have come to realise that my writing does in fact require a healthy break from all the churning and rumination. That I need to take a step outside my own stories and write about joy – queer joy, gastronomical joy, Nepali joy, musical joy, joy from the exterior world.

There seems to be a consensus about setting healthy boundaries in poetry. It is to create a conscious separation between you and your poetic or authorial self. This idea reminds me of something Judith Butler wrote, in Giving an Account of Oneself: ‘The narrative must then establish that the self either was or was not the cause of that suffering, and so supply a persuasive medium through which to understand the causal agency of the self.’ The healthy boundary is to know that the ‘self’ that writes is separate from the ‘self’ that just is. I am beginning to learn that a poem cannot and does not claim all of me at all times. I am learning that, as Toni Morrison says, ‘I am not my work’.