We spoke to Kieron Gillen, writer of such comics as Phonogram and The Wicked + The Divine, to get the writers' perspective on working in the comics industry.

Why did you want to write comics? Apart from the obvious, what do you think distinguishes the Comic Book and Graphic Novel from other mediums of storytelling, what do they offer that other mediums cannot?

I came to comics late. While I'd read them as a child, I'd drifted away in my teenage years and approached them as an adult. It was instantly enchanting. I normally say – “imagine at the age of 25 you discover pop music. You realise that it's been going on for about one hundred years and there's whole shops full of this stuff for you to explore.” To discover a whole art form you know basically nothing about at such a later age is a joy. I came to it with all the enthusiasm of a convert, and tried to catch up. Within six months I was writing my first scripts.

I came to comics late. While I'd read them as a child, I'd drifted away in my teenage years and approached them as an adult. It was instantly enchanting. I normally say – “imagine at the age of 25 you discover pop music. You realise that it's been going on for about one hundred years and there's whole shops full of this stuff for you to explore.” To discover a whole art form you know basically nothing about at such a later age is a joy. I came to it with all the enthusiasm of a convert, and tried to catch up. Within six months I was writing my first scripts.

The appeal for me is on the formalist level – I Iike writing work for the form, and about the form. Comics offer some of the advantages of prose and some of the advantages of film, and a whole bunch of their own limitations. When starting to consider my work, I always consider “will this story actually work best as a comic or not?” It's not always true.

They also offer the rarest of things: there's still the opportunity and space to actually define the canon. I love prose, but you're never going to be Joyce, even if you're as good as Joyce. In comics, the canon is more fluid. If you want to play for that, you can. I'm far too trashy to aim at that, of course, but always good to have the option.

You've had a few titles published by Image Comics, but you have also worked for Marvel Comics. Can you explain the differences between Image Comics ‘creator-owned’ model and the Marvel model?

On the crass commercial side, Marvel is strictly work-for-hire with an incentive payment. It's the same as any form of writing like that. Image is more akin to the traditional book deal. We get an advance on the book, and we keep ownership. Image is an unusual deal, but it's probably best to think at that. There are also different models of ownership in comics as well. The easiest way to think of it is the equivalent of writing for a licensed property and writing for yourself.

What are some of the advantages and disadvantages of working for a creator-owned publisher, versus working for one of the ‘Big Two’? Do you think creator-owned publishers will ever be able to compete against the ‘Big Two'?

Well, I say advance above? Advances are variable, and sometimes non-existent. With working for the Big Two in a work-for-hire capacity, you get the page rate so you can eat. Eating is nice. The main advantage is that, as a writer, you have the flexibility to dance between the two at once. I basically do four issues a month. For a long time, the work-for-hire supported the creator owned stuff. I'm lucky enough that my work does well enough that's no longer true, but it's often a case that one pays for the other, at least in the short term.

Well, I say advance above? Advances are variable, and sometimes non-existent. With working for the Big Two in a work-for-hire capacity, you get the page rate so you can eat. Eating is nice. The main advantage is that, as a writer, you have the flexibility to dance between the two at once. I basically do four issues a month. For a long time, the work-for-hire supported the creator owned stuff. I'm lucky enough that my work does well enough that's no longer true, but it's often a case that one pays for the other, at least in the short term.

One interesting thing in comics is that due to its own history bouncing between licensed and your own work isn't quite the scarlet letter it is in prose. Same with self-publishing in comics. As traditional publishers had no interest in comics for the majority of its form, much of the serious work was originally self-published. It's an interesting case study of how things change.

I admit, it suits me. I like that I'm free to bounce between writing pop and literature, for want of a better phrase. I get bored terribly easily, especially when I have to pretend to be a grown-up 24-7.

Will creator owned publishers ever compete against the Big Two? Honestly, it depends on the lens you're looking through. The biggest selling graphic novel of this year won't be from the Big Two – it'll be Raina Telgemeier's Ghosts. Marvel and DC's monthly market tends to dominate perception of what people think of as comics, but it's always more complicated than that. Image is the third publisher in single issues, but they do very well in trades – and even in singles, individual books can match most books from Marvel and DC (Saga and The Walking Dead, for example).

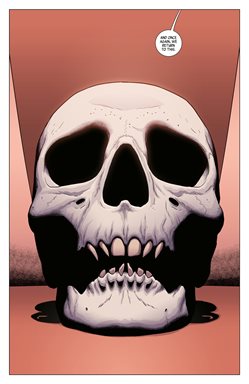

The issues of The Wicked + The Divine, the book I'm probably best known for, does a little less than 20k, which is low for a Marvel book... but last time I looked we've done over 100k in the trade collection of the first collection. Then we can talk about digital and... well, it's just more complicated.

Comics have become more accessible to newer readers because of digital distribution. But recently Comixology created an unlimited subscription service (US only) for a monthly fee - Marvel already has its own unlimited service. How will this affect your business as a writer?

Good question. I suspect we'll find out. The Comixology service is primarily a way of attracting new readers, as it only offers the first collection in a series. As such, they'll read the first for free and hopefully buy later ones – though there's a payment via the Comixology subscription. The Marvel unlimited service is a different beast, offering a large portion of Marvel's back-catalogue with a six-month time lag, but Marvel is work primarily paid as work-for-hire rather than sales of work.

There are characters in The Wicked + The Divine that have obviously been inspired by well known, influential artists and throughout your comic book career you have written for characters who have similarly impacted western culture (Darth Vader, Captain America and The X-Men). What is it like to write characters who are not only created by someone else but who already have a well-established and popular mythology?

It's an interesting challenge. Partially it's like writing your take on myth, especially with the biggest characters. Most people know what Spider-Man or the Hulk is like, in the same way they know what James Bond or Robin Hood or Hercules is like.

It's an interesting challenge. Partially it's like writing your take on myth, especially with the biggest characters. Most people know what Spider-Man or the Hulk is like, in the same way they know what James Bond or Robin Hood or Hercules is like.

The other side is the part that's more like writing a historical novel. They may be fantasy worlds, but there's an established history, and you're trying to integrate with that. My Darth Vader run with Salvador Larocca is set between A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back and basically involved a close reading of that whole period in the canon, and working out what the logical story to bridge the two would be.

But there's a varying level of flexibility. Marvel's history is much more flexible. Originally, Iron Man became Iron Man in the Korean War. Over the years, that's been tweaked to keep him more contemporary. Working out what needs to change to speak to the present day is a big part of the job.

Is it always easy to bring something new to these characters?

Hell, no. But that's the job. Working ways to critically attack a character and working out what, if anything, there is to do. When a publisher asks me to write an already existent character, I just dissect them. What's really going on? What's interesting about them? If I can't find a way to make myself care about them, I just don't do it.

The artist Jamie McKelvie is a long-time collaborator of yours. How was that relationship built and how has it developed since you first collaborated together? How do you write for McKelvie? Are your scripts detailed or do you give him more freedom when it comes to interpreting what you have written?

Relationship is certainly one word for it.

We met in the British small press scene in the early 00s, where apparently the second sentence I said to him was “Hey – I've got an idea for a comic called Phonogram and I think you'd be the perfect artist.” A chance meeting which neither of us have managed to escape from.

We met in the British small press scene in the early 00s, where apparently the second sentence I said to him was “Hey – I've got an idea for a comic called Phonogram and I think you'd be the perfect artist.” A chance meeting which neither of us have managed to escape from.

My scripts to Jamie could be less detailed, but it's rarely true. Partially it's an element of what I wrote above – I'm interested in writing comics, and if I'm not at least having an input on execution then I'm not really writing comics. I'm writing a story which an artist is then interpreting into comics. There are people in comics who do work like that, but I'm a formalist.

So Jamie has to suffer through all manner of ill conceived ideas, which we then debate over. My scripts to Jamie are conversational, and something we regularly say is that the Script is a proposal rather than a blueprint. It's the start of a conversation rather than the end. We text each other questions, ideas, variations.

There are certainly some areas of the script I leave more open than others. When we're in a strict grid, I tend to get metronomic and precise. Other sections I write in Marvel Method. That's a method invented in the 60s, where rather than writing what happens in every panel, the writer describes the events and the artist interprets, and then the writer goes back and adds lettering. As you may imagine from what I've said above, my Marvel Method isn't really like that – it reads more like a commission, where I describe an approach that doesn't readily break into traditional panels. I also include at least a pass at dialogue in it.

For Jamie, it's important. He's not just an artist – he's a writer. His own Suburban Glamour is great. For him to do what he does, he needs to know the interiority. Some artists I'd just write “Character smiles.” With Jamie, I'll add why they're smiling, and all the subtext and everything else. Jamie is an incredible actor. He inhabits the character, and I write for that. I'm happiest when I delete lines of dialogue as Jamie's drawing does the work the story requires.

What are you currently reading?

I finished Charlotte Gordon's Romantic Outlaws a couple of weeks back, which was just wonderful. I've just started Alan Moore's Jerusalem, which I plan to take my time with. I'm also reading Sylvia Patterson's memoir on music writing, I'm Not With The Band. I'm only in the early days, which are joyous, and am dreading the slow descent of music writing across the decades. In terms of comics, I'm following a worrying number of things – the latest ongoing which struck me as really interesting was Hickman/Coker's Black Monday Murders, which is just this fascinated twisted piece of formalist murder mystery. I also finally got around to reading Raina Telgemeier's breakthrough Smile. I'm not someone who is particularly drawn to Young Adult work, but I found it really strong. I'm going to be interested to see what the generation of people she inspires end up doing.

What comic books/graphic novels would you recommend to new readers?

I don't really have any generalised recommendations. Honestly, it's just too open a question. Imagine if you'd asked me “what books and novels would you recommend to new readers?” Clearly the answer would be “It depends what sort of work the reader is interested in” and the same is true here. The good thing about comics in 2016 is that you can give an answer no matter what someone's interests are. The Anglophone comics world is clearly smaller than novels, but there's at least some work no matter what your interests are. If someone enjoyed modern crime, I may suggest Criminal or Stray Bullets. If someone was interested in the literary mode of memoir, I may suggest Fun Home. In terms of people reading this article in this venue, I suspect I'd suggest McCloud's Understanding Comics. It's a comic about comics, how they work, what they do, etc. If someone has a generalised interest in comics and learning what on earth is going on with them, it's a strong place for any critical thinker to start.

Kieron Gillen has been writing for Marvel since 2008, and has pretty much played with all the major icons now, for at least a panel. His comics include Thor, Journey into Mystery, Uncanny X-Men, Iron Man and many more.

Kieron Gillen has been writing for Marvel since 2008, and has pretty much played with all the major icons now, for at least a panel. His comics include Thor, Journey into Mystery, Uncanny X-Men, Iron Man and many more.

His Marvel work for 2015 included Darth Vader and Angela. At Avatar Press, he is writing the incredibly serious WW2 superhero book Uber and Mercury Heat.

His other works for Image include Spartan Slave Hunt story, Three.

Read more